|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

University Business Daily UB Exec Arts & Letters Daily Academic Partners Subscription Services Advertising Information Copyright & Credits |

I'VE BEEN INVITED TO JOIN a freshman composition class at Mott Community College in Flint, Michigan. I live in New York; we're going to be meeting halfway, in Mushville. I was told to take the Internet and get off at palmer.sacc.colos tate.edu 6250. My beat-up Mac gets me there in a couple of seconds. This is what I see: A large cornfield ringed by trees, somewhat misty around the edges. You notice that there is a cheery bonfire in the middle, surrounded by large logs perfect for sitting on and roasting marshmallows... I walk into town; there's no one around. I'm a few minutes early. The town runs along a north-south street. I read signs pointing to the park, the library, a theater, and something called Writer's Block Café. I wait for velo to appear. Velo is a se ntient bicycle -- red, with shiny fenders. It is also the Mushville persona of Steve Robinson, the teacher running the class (which should be here any minute now). He warned me that he might be late -- he still has to help some of the students log on. I am waiting for velo and his class of thirty students in a MUSH called WriteMUSH. A MUSH is like a MOO, which is like a MUD. A MUD is a multi-user dungeon -- a computer game. MUSHes (Multi-User Shared Hallucinations) and MOOs (MUD Object Oriented) are mo re fluid than games -- they are virtual towns, or clubs, or cafés, or frontier lands, whose rules and personalities evolve over time. What makes this possible is the Internet. MOOS, LIKE E-MAIL, work through computers linked by phone lines, but unlike e-mail they allow users to have real-time, multiparty conversations rather than just leave messages for each other. Logging on to a MOO is like walking into a vi rtual room in which you find a number of objects (a description of the space is written into the program) and other people, sometimes hundreds of them, who are sitting at their terminals, logged on to that MOO, at that moment. The first MUDs were built around 1978. At the time there was a popular text-based adventure game called, appropriately, Adventure, which ran on a university computer. At first, players played alone, against the machine, going from room to room collecting treasure, killing monsters, until they eventually won the game. After a while it got boring. Computers are predictable. So a few programmers decided to network several games and let people play together, simultaneously. Then, something unexpected happene d. People no longer played to win the game; they now played to be with other people. A virtual community began to form. There are now more than 400 of these MUDs and their descendants running on the Internet. MOOs are significant because their creation allowed users to build their own rooms and write their own programs within the virtual world. MUDs were fixed places, most definitely games; MOOs took control from the head programmer and distributed it to every user. The point was not to play a game but to build a social space in a permanent state of evolution. I get fidgety waiting for velo and his class and decide to explore Mushville. I head north, up the street. I pass by a church, a pizza parlor, a school. Up ahead is a lighthouse and the beach. The beach is the end of this part of Mushville. It doesn't hav e to be -- Mushville could go on forever -- but over the years, virtual architects have learned to use boundaries. People like them. It keeps the space intimate, real. Trying to go farther north than the beach dumps you in the ocean: You find yourself swimming in the restless ocean, the waves moving you effortlessly, the sun warm overhead. The ocean moves in a long, soft wave of sound, a great rushing, like wind through a thousand trees in a long, calming rush. Going any farther is impossible. I swim back to shore and stare out to sea. You find yourself captivated by the view and feel as though you were able to join the seagulls in flight. You are reminded of your earthly ties by the lapping of the waves and the fishing boats bobbing upon the ocean waves. As I look out at the fishing boats bobbing on the waves, Teldorn pages: Hi there. I go back to the town square, hoping Teldorn (one of velo's students) will be there -- I want to know where the class is. Teldorn must have checked to see who was logged on and found me. Teldorn and I bump into each other in the town square. He offers t o take me to class, telling me that the students are at last arriving. As he speaks, a steady stream of characters hurry past us: Bruno, niki, Smurf, kurt, Ronda. It is a virtual stampede. They are headed to school. The school is a block north, sharing an intersection with the church and the pizza parlor. You go up the stairs and into the school. I type,go class You open the doors and head into class. I find myself surrounded by students busy transforming themselves from character to character, poking at each other, and asking me what I am doing here. I tell them I was invited by velo to sit in. By the time velo arrives, I have gathered that he wants t hem to write an argumentative essay. He divides us into small groups and sends us off into different rooms to discuss it. I find myself with Jasmine, crista, and tanis the elf. Jasmine is studying business administration, crista is preparing to be a paralegal, and I can't figure out what tanis wants to do. He may be a netsurfer who has come to crash the party. I type, look at Jasmine, and I read this description: Jasmine is looking very smart today. She is wearing a white silk blouse and button fly Guess jeans. Her hair is pulled back, showing off her emerald earrings. She returns your look with a friendly smile. I check crista's prose: red hair, light tan, wearing blue jeans, western boots, and a western shirt. Telegraphic; reminds me of the personals. I wonder if these are cross-dressers. I ignore the elf. I ask them what their essays are on. Jasmine is very talkative. Her title is "Not All Pit Bulls Are Vicious Animals." I agree. Crista won't answer the questi on, so I ask her again. Finally she says, I really can't think of what I could write about. I'm not one to put up an argument on anything. I try a different approach: Crista, can you think of anything you disagree with?For the next few minutes she is very quiet. Jasmine and I discuss why she likes using MOOs as part of her education. Then crista drops a whopper i n my lap: crista says "I really don't like mixed marriages, but that would offend my sister. I'm not against blacks, I have made lots of friends that are black, and I like them." I wonder why crista told me this. It's not the kind of comment one makes in casual conversation with strangers. I ask what it is about MOOspace that leads people to be so direct. Jasmine says "well it is a time to be alone and yet be with others you can let down your guard and share things, or act in ways you wouldn't normally do." Tanis the elf smiles. WHEN I STARTED RESEARCHING this article I had no experience with MOOs or MUDs or M-anythings, but I understood what it was like to be totally absorbed in a text-based reality. As a kid in the early 1980s I used to play a variation of Adv enture called Zork on my Atari computer. This led to Zork II and III and a steady stream of convoluted fantasy games with names like Deadline and Planetfall. I became obsessed with them, spending months at a time solving puzzles, trying to get to the end. I'd pick up another game and keep going. I'd swap tips with friends. It was a way of life for a while, a sort of living science-fiction fantasy. I abandoned it when puberty diverted my interests elsewhere, and not until last December did I come back to t hat world: That's when I opened an Internet account from my home in Manhattan ($20 a month) and canceled cable television to pay for it. Ignoring all other Internet distractions, like newsgroups and e-mail, I headed for the closest MUD, a place called Thu nderdome. This is a classic hack-and-slash game, except unlike in Zork, Planetfall, and all the rest, there were other people all around me. It was a strange sensation. I felt very happy. I canceled my appointments. I had people to meet, places to go. But a day later I experienced something unexpected, the last thing I ever thought I would feel in something as cool as a MUD: boredom. I kept ac costing players named Ranger, Black_Knight, and Black_Magik, asking them where they were from. Answers like "the castle" and "Lórien" (a forest in the Tolkien books) just wouldn't do. I kept prodding, accusing them of taking this all too seriously. After all, isn't this a game? I didn't want to talk about slaying trolls. I got yelled at (as much as one can yell with text). I was shunned. I ruined the party. I was back-stabbed by a thief. My character, named Bored, was assassinated. Then a few days later I telephoned Jennifer Grace, a cultural-anthropology graduate student at Duke University who studies virtual communities. Jennifer does not spend much time on MUDs -- she does all her research on MOOs. She warned me that this kind of research quickly bleeds into your real life, taking it over. Everything in a MOO begs to be catalogued by an anthropologist, because people in MOOs come there to be with other people. They do not decapitate elves -- they socialize. They lie. They become painfully earnest. Since I'm a former practitioner of anarchic improv comedy, for me the lies became theater. In a MOO, the lying is role-playing, turning MOOs into wild metaphorical playpens where subtext becomes preposterously magnified and released. Th ey are a strange surrealist hybrid of the sweetness of self-help and the raging braggadocio of hacker subculture. When I spoke with Jennifer the first time, our conversation was very serious -- no jokes allowed. Jennifer didn't seem like the kind of person you'd want to get drunk with in a bar. That is, until I did, at least virtually speaking, when she invited me to join her at Club Dred on LambdaMOO. Lambda was the first MOO. Lambda is the biggest MOO. LambdaMOO is a wonderful dance to witness. To enter Lambda is to visit the hive of the reigning MOO Queen. Like some giant, overstuffed termite mom, Lambda is fed and fattened by a small horde of slave workers. In return, Lambda's parent, Xerox, gives anyone who wants it free access to the MOO sof tware -- a policy that has bred the MOO infestation that now riddles the Internet. Xerox is studying the future of networked virtual realities, a technology that didn't exist four years ago, by giving the software away and letting overeducated hackers imp rove on it. The slave workers are computer types of various kinds -- students, postdocs, Xerox PARC employees -- who voluntarily manage the 8,000 or so permanent characters on Lambda and vainly try to track new additions to the 5,000-plus "rooms" that mak e up the hive. The slaves are called wizards -- a term left over from hack-and-slash days. These wizard/slaves wield a magic wand: the programmer's bit. Ownership of a programmer's bit allows a wizard (or even a puny Lambda-mite, if she is given one) to program new kinds of objects into LambdaMOO. People with bits are cool. People who give out bits are even cooler. To add to the insanity of the mix, the father of the Queen, Pavel Curtis (a.k.a. Lambda and Haakon), Xerox employee extraordinaire and creator of the MOO software, permitted Lambda to become a democracy. Now even newcomers like me ca n vote on various propositions, like *Ballot:mpg (#75104): 'Minimal Population Growth' (I voted no on that one -- I want the population to explode). The irony of this is ignored. This is not a democracy. LambdaMOO sits on a hard drive in the belly of the Xerox Corporation. A little tug and the plug comes out. To log on to Lambda, I type, telnet lambda.parc.xerox.com 8888 into my Internet account. All that means "Get me over to Lambda, now." PLEASE NOTE: I type, connect solomon joviso and I get this annoying message: *** The MOO is too busy! The current lag is 14; there are 182 connected. WAIT AT LEAST 5 MINUTES BEFORE TRYING TO CONNECT AGAIN! *** Five minutes. Forget it. I speed-dial, immediately cycling through ten attempts. Finally the lag dips below five -- the magic pressure level -- and I'm in. The connect solomon joviso tells the Lambda computer to let me in as Solomon (my Lambda character); "joviso" is my password (not anymore, for you hackers out there). That little word "lag" is the bane of the virtual universe. It is an omnipresent subject of conversation. As the termites multiply, the hive they crawl in -- disk space and processing time -- gets crowded. The Xerox computer tries to serve everyone, stacking us into a huge queue; the time between an entry request and the computer's completing it is the lag. Sometimes it goes up to 40 seconds. That's when it's time to go to one of the other 400 M-whatevers out there. I tumble into Lambda and straight into a coat closet. The lag is approximately 3 seconds; there are 178 connected. It's a good thing the closet is dark. Those other people (apparently sleeping) are the 7,922 souls not currently logged on. The closet is where Lambda stores virtual corpses. With the lights on, you'd have to sit through a long list of sleeping names scro lling down your screen. That would really make the lag bad. Some cool MOOers build their own, personalized rooms, and when they log on to Lambda they appear in them. It's eerie to walk into someone's room and find him there sleeping. Unfortunately, Lambda MOO prevents you from wreaking any mayhem on the sleeper, but you can build objects and leave them behind, like love notes and flowers. First-time users connect as guests by typing connect guest guest, where "guest" serves as both name and password. Since the name "guest" is usually already taken, you wind up with some modification of it, such as Blue_Guest. Makin g your own character is easy. I type, @request Solomon for davidsol@panix.com. A few hours later LambdaMOO e-mails me confirmation that no one else has the name Solomon, and gives me a password. Now I'm Solomon. The @ sign means t hat what follows is a computer command. I am essentially programming. To be a name without a description is unacceptable. When people type look at Solomon they want to see what I look like. Associating a description with my name is equally simple: I just type, @describe me as . . . and then whatever I want my description to be. If you were to look at me, you would see: Solomon is a little stressed out from being indoors too much, but happy to be here. Wearing a jacket, shirt, and jeans with heavy brown shoes. Tall with disheveled black hair. He is awake and looks alert. The final product requires gender -- male, female, or neuter (I met a giant carrot the other day; it was neuter). To give myself my gender I type, @gender male. That's it. That made me Solomon. More advanced players create a set o f names and descriptions, each very different. Cycling through them is called morphing. Now, after a few weeks on the MOO scene I am not only Solomon -- I am Pepe, chia_pet, and my_little_pony. But Solomon is my parent character, my first MOO self. The ot her characters come in handy, depending on the situation. Pepe is a six-foot-tall, oversexed French skunk, chia_pet is a quiet 400-pound plant, and my_little_pony is a very sweet, sincere, two-inch-high pink plastic toy. Typing open door will get you out of the closet and into the living room. The people in the living room will see on their screens the words Solomon comes out of the closet (sort of). The living room is the heart of Lambda. The ori ginal space was designed to look like a California house, the kind a successful Palo Alto Xerox employee might have. It has a pool, a hot tub, a kitchen, a dining room, and lots of bedrooms. Things have changed since then. Under the pool there is now a wa rren of caves filled with a couple of headless elves and hack-and-slash knights, but don't tell the neighbors. Stare too closely at the postcard of Paris on the fridge and you'll find yourself tumbling into it . . . and out onto the Boulevard St. Germain. Outside, past the garden by the pool, is a path leading into deep South American jungle. Flights to Brazil leave from there. As long as there is disk space, there can be rooms. Build a room, convince a wizard it's good, and he (rarely she) will link it u p to the rest of the MOO for you. There are a lot of half-finished rooms sitting in limbo in Lambda's memory, waiting to be connected -- only they never will be. They are abandoned. As a character you can do three basic things. First, you can speak, by typing "Hello. The computer takes the double quote mark as an instruction to print what follows it as speech, so that other people in the MOO room see Solomon says "Hello." Second, you can emote. Emoting allows you to take on a narrative voice and show emotions, actions, thoughts. If I type, emote yawns loudly, what you are saying is tedious, the computer prints out, Solomon yawns loudly, he thinks what you are saying is tedious. Third , you can build -- anything from rooms to virtual accessories. Building rooms is easy. It's the same as making a character, except here the name is associated with a "space" (on the Internet, space is a rather abstract concept). Once the space has a name, associate a description with it and you have a room. You can t hen create objects to place inside the room, like newspapers, cookies, chairs -- anything you can think of. You can also program a set of verbs to go with each object. I was in the kitchen speaking with Freya and du_Nord when Grump, a person in another ro om, commanded the housekeeper to deliver a plate of cookies: At Grump's request, the housekeeper sneaks in, deposits plate of cookies, and leaves. I type, eat cookies You eat one of the cookies on the plate. The verb "eat" was associated with the object "cookie." Typing eat cookies (I wanted all of them) prompted the computer to describe me eating one. I could also have typed take cookies and then give cookie to du_Nord. In each case the computer would have understood what I wanted to do, because the creator of the room programmed it to respond to the verbs "eat," "take," and "give," among others. The housekeeper in this case was not a real character but a robot programmed by the room's creator to perform ce rtain actions. Between the rooms, the robots, the objects, and the characters, you have a complete text-based virtual reality that evolves over time, creating history and a virtual community. MOOspace exists only as text flowing down your computer screen. Sometimes I spend eight hours at a time staring at the moving words, typing back at the people typing at me. My mind has accepted that this is real. As Jennifer warned, the "research" took ov er my life -- for a few weeks I logged on every day. It also brought me closer to Jennifer. The nerd on the phone became an alluring woman named amazin (as in amazin Grace) in Lambda. Ours became my first MOO friendship. Now I spend several nights a week with her. She has become a confidante. That's the strange thing about MOOs -- they pop up like trapdoors in your life and connect you to people you would otherwise have nothing to do with. All the context that separates two people like Jennifer and me dis appears, leaving an illusion of intimacy: an intimacy devoid of life's accessories, the baggage that we carry around with us. Some MOO friends try to take a relationship out of virtual space, but veteran MOOers are wary -- they've been burned too often by net friendships that collapsed once the stuff of real life came in. I was sitting in the Lambda living room when I received a page from amazin. Paging is a way of speaking to people not in the same room with you; it's also a way to keep messages private. I found her in Club Dred. amazin pages, "type @join amazin" I type, page amazin with "okay" amazin hears you and smiles sublimely. I type, @join amazin You visit amazin. This is the kind of detail that keeps people coming back. That and the robots -- like the bouncer and Abigail, the waitress -- that seem human. Typing order milk from Abigail will get you just that, a glass of milk. And that glass can be passed around, c hugged, sipped, thrown. In this world, writing defines your position in the social hierarchy. Good writers, intelligent writers, get lots of attention. Your sex appeal depends on your prose. I look at amazin. amazin is a 5'4" buxom blonde with grey-blue eyes and a soft pageboy haircut. Jennifer has told me she is short and heavy IRL (in real life). That phrase, "IRL," comes up a lot, to separate what happens in MOOspace from out there. I don't believe there is actually a difference between real life and MOOspace -- especially when you s pend most of your waking hours in a MOO. Then again, I am a novice. I haven't been burned yet. Some people cling to this IRL distinction not because they've been burned but because they prefer not to acknowledge the humanity of the person behind a character. That way the whole experience remains separate, compartmentalized, dehumanized. MOOers lik e that can be abusive -- groping you, hitting you, making fun of you. For some reason MOOs bring out that kind of behavior in many people. Because of that, many MOO users cloak their gender and race. I've noticed that a lot of guests are women -- they com e on as guests to be left alone, keeping their gender hidden. Others cross-dress, claiming they are male when they are female IRL. But more often than not it is the IRL males that come on as females. I still don't understand what it is that excites men ab out coming on as absurdly oversexed Jessica Rabbit female clichés. One MOO pastime is "outing" cross-dressers. Their prose often gives them away, as in the case of the "homosexual woman" I met in a hot tub at LambdaMOO. Everyone in the tub with us picked up on her description, screaming, "A lesbian would not call herself a homosexual woman." She turned out to be a teenage boy. SOCIAL MOOS LIKE LAMBDA outnumber all other kinds. Their growth has been so rapid that some colleges (Amherst, for one) have outlawed MOOing from their computers. At one point Australia banned MOOing altogether -- the MOO load on its few long-distance trunk lines was so heavy that "legitimate" activities, such as currency trading, had slowed to a crawl. The range of social MOOs is endless; some are completely unrelated to anything in real life. The FurryMuck is a MOO where half-human, ha lf-animal creatures come together and have netsex -- usually a process of rapid one-handed typing. BayMOO is a squeaky-clean Bay Area MOO where emote lights a cigarette and takes a long drag gets you in big trouble. Dhalgren MOO is postapocalypse New York City, where dogs run wild and street hustlers try to make you part with whatever virtual currency you may be carrying. And then there are the professional MOOs, the ones intended for teaching and research. These are struggling to become more than curiosi ties; they want to be useful. MediaMOO and BioMOO, for instance, are serious MOOs used mainly by researchers to share information, network, and exchange job tips. Job listings cover their virtual bulletin boards, electronic greeting cards are swapped, research ideas shared. Unlike wit h e-mail, there is an element of serendipity to MOOs -- maybe you'll run into someone unexpected, with useful information. MediaMOO was created by Amy Bruckman, a graduate student in the Epistemology and Learning Group of the Media Lab at MIT, in the fall of 1992. Bruckman held an inaugural ball for the MOO on January 20, 1993, that competed with that other inaugural ball in Washington, D.C.; some 400 celebrants attended the virtual dance. Now, more than 1,000 people -- mostly professors and students of c ommunications and researchers in corporate labs -- have permanent characters there. To have a permanent character on MediaMOO, you must submit an application that is reviewed by a committee of seven MediaMOO users; if two vote no, you are denied a permane nt character. Like many other MOOs, MediaMOO is in the process of becoming a democracy. Bruckman no longer makes all the decisions; running MediaMOO is now up to elected officials, chosen by members in a secret ballot. MediaMOO's most popular event is the Tuesday Café, which thirty or more people log on to every Tuesday night for a discussion. Tuesday Cafe BioMOO is based in Rehovot, Israel, at the Weizmann Institute of Science. It contains a laboratory filled with virtual machines that can manipulate virtual atoms, combine virtual enzymes, code virtual proteins into RNA, and display periodic tables. Anyone can log on to BioMOO and use it as a gateway to supercomputers around the world. I was given a tour by Gustavo Glusman, a graduate student in biology at the Weizmann Institute and BioMOO's founder, whom I found in the woods outside the biology building. Glusman explained that while BioMOO was a professional space for biologists, anyone could have a character here. Everyone with a character enters a description of his or her research interests. I started checking through lists and found descriptions like this: Isolation and characterization of the DNA encoding the 5' end of the human/gabaa benzodiazepine alpha-1 subunit gene. Characterization of the promoter and control of gene transcription. Later I found the scientist whose description this was; his BioMOO name is Martin. IRL Martin is Martin David Leach, a graduate student at the Boston University School of Medicine, where he is working on his Ph.D. in molecular pharmacology. Martin's bifunctional office (MBO) Scientists have a rough life. I type a few toilet jokes and we move on. Martin asks me if I want to see the machine he built in the lab, which analyzes genetic sequences. I say yes. This database is a search facility for scientists who want to compare a protein or DNA sequence they isolated in a lab with known sequences store d in large databases around the world. The idea is that a scientist who discovers a genetic sequence can find out whether someone else has already catalogued it. Martin gives me a sequence to type in: agatcagcgactgactgactatcatcagagacac. I send my sequence off to the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), a computer in Heidelberg, Germany, for analysis. EMBL is supposed to e-mail me the results in a couple of hours or days. In addition to research and informal-networking MOOs there are many virtual classrooms in academic MOOspace. Some, like those in MUSHville, are components of small-time, relatively simple MOOs. Others borrow space in a large, complex MOO called Diversity University. This MOO is a virtual campus: DU's founder, Jeanne McWhorter (who is getting her master's degree in social work from the University of Houston), built the streets and buildings, and offices and classrooms spring up as users require them. This is what the campus looks like:

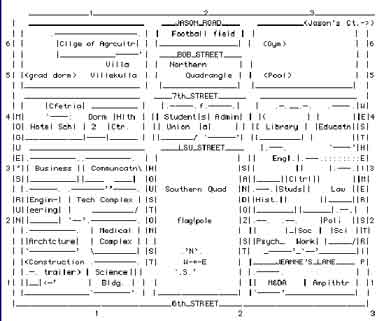

Without this kind of structure, MOOs quickly sprawl outward, following the contours of communal fantasy. Many find this element of MOOs exciting. So what if you pass from a closet to a cloud to a bar? This is a virtual world. In MOOs like DU, though, crea ted for professional purposes, structures are useful. Anyone can log on to DU, including students not registered in any classes. For now, use of DU is also free. To prevent uninvited guests from crashing, teachers can "lock" rooms to users who haven't asked their permission to enter. DU students are mostly A merican, but there are some Canadians as well. As the number of Internet nodes expands internationally, DU plans to create virtual events linking students around the world. At the moment there are no students attending DU or any other virtual university e xclusively. That may change soon with the creation of GNA, the Global Network Academy. GNA is vying to become the world's first accredited virtual university. Incorporated in the state of Texas in November 1993, GNA hopes to graduate its first degree-holding class by 2005. This April, GNA will begin teaching its first extension courses. Cla sses take place in a virtual campus, which is really a link between four different MOOs: Diversity University, MediaMOO, BioMOO, and the GNA lab. GNA contains a virtual library, which is a keyword-searchable index of information on the Internet, and which will make texts in the public domain available for course work. At the moment GNA offers only two courses -- Introduction to the Internet and Introduction to Object-Oriented Programming Using C++ -- but in the future it will offer Renaissance Culture, In troduction to C Programming, and creative writing. Until copyright laws clearly define how electronic media should be billed for and distributed, virtual classes are limited to subjects whose texts tend to be in the public domain -- subjects like math, wr iting, and "the classics." CYNTHIA WAMBEAM, AN INSTRUCTOR at the University of Wyoming, is one of the fifteen teachers who is borrowing classroom space at DU at the moment, and she has designed the courses she teaches there to double as investigations into the eff ect of virtual communication on writing. Wambeam teaches two freshman composition classes of twenty-three students. One uses the MOO; the other -- the control group -- does not. Both sets of students are required to keep journals. The control students wri te their entries in notebooks; the MOO students post theirs on an electronic bulletin board. Wambeam devised this experiment with Leslie Harris, an assistant professor at Susquehanna University in Pennsylvania. What Wambeam and Harris want to know is: At the end of the class, which group will be better writers? At the end of the semester, all for ty-six students will write an essay, and several outside evaluators, who do not know which students were in which group, will pore over the essays and try to discern differences in the students' prose. (Their results will be presented at the Computers and Writing conference in Missouri in May.) Harris has found, in his own MOO classes, that computer mediation changes the nature of classroom dialogue: The role of the teacher shifts from conversation controller to facilitator, and the students have to take charge of the discussion. Harris is askin g his sophomore-level Western-literature students to re-create Dante's five levels of hell in MOOspace. The class is divided into five groups, each of which is programming a different level of hell, complete with scenery, characters, and dialogue, and wil l then perform the piece for the other groups. Students will view the performance from computers scattered around the campus, following the story as it appears on the screen -- a textual theater. All this is supposed to give them an intimate experience of The Inferno through reenactment. AT BROWN, ROBERT COOVER teaches hypertext fiction in a MOO called the Hypertext Hotel. Students create virtual rooms in the hotel, each of which is a story, which can be added to by other students posting new text there. Since the hotel is on the Internet, they can also be added to by the MOO public. Usually "hypertext" describes writing where there is a dynamic link between two or more texts: Clicking on a word in one text transports you immediately to another text, from which you can c lick on another word and arrive at yet a third text. The Hypertext Hotel is more static than that -- it is really just a conventional MOO, where each room contains a story instead of a description. Coover says the hotel is meant to be "playful, not a grea t literary document," and in fact the "stories" posted there are less experimental fiction than a kind of cyber-toilet-stall graffiti. Room names read like subheadings in a De Sade crib -- titillation, abstinence, prostitution, quietude, servitude, necess ity, electrocution, gesticulation, malnutrition, flotation, perambulation, and so forth. I type, follow titillation You enter titillation A few users of the hotel, led by hypertext-fiction author Carolyn Guyer, are trying to reclaim some literary integrity for it. Guyer has created "Hi-Pitched Voices," a wing of the hotel that has somehow remained free of graffiti. I wandered around there, through rooms with names like "want," "inspiration," and "mouth." follow mouth The text scrolls down my screen, waving from side to side as it appears. The movement is a surprise -- it is even a little eerie -- but otherwise the poem is obviously pretty bad. Coover agrees that much of the stuff in the hotel is bad. The lack of edito rial control, he has realized, leads to a reading experience that is "very diffuse, and seems totally undirected, and is finally kind of a bore to move around in." As is the case with other MOOs, the very things that make the medium interesting -- easy ac cess and unrestricted participation -- have also made it boring. Coover hopes that the hypertext created in the hotel will at least hold some sort of historical interest for future literary theorists. "Maybe thirty years from now, it will be like the Mick ey Mouse watch," he suggests. "Maybe it will retain a kind of aura of its time that people will find compelling." JOHN UNSWORTH, DIRECTOR OF the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities at the University of Virginia (an organization started with a large grant from IBM intended to foster and develop computer-mediated research in the humani ties), first used MOOs to teach composition classes at North Carolina State University at Raleigh. He has since become famous in certain circles as the creator of the Post Modern Culture MOO, or PMC. As far as Unsworth knows, PMC is the only MOO affiliate d with a peer-reviewed electronic journal in the humanities, the journal being Postmodern Culture, whose editorial board includes such luminaries as Kathy Acker, Henry Louis Gates Jr., bell hooks, Avital Ronell, and Andrew Ross. PMC is meant to be a serious MOO, a social space for intellectual discussion. It contains a library from which you can get articles from the Internet, a coffeehouse for casual conversation, individual rooms built by members, and a central lobby where ever yone arrives. Discussion covers issues like "embodiments" and "cyber-subjectivity." PMC-MOO is frequented by pomo types of all ages -- highschool students, graduate students, professors -- and on any given night forty or so can be found there. I logged on as a guest, hoping to find out what Post Modern Culture means. PMC-MOO is a virtual space designed to promote the exploration of postmodern theory and practice, a place for intellectual meandering. Here, we mix the unstable "real world" of postmodernity with the solid virtuality of MOOspace. *** Connected *** Although twenty-one people were logged in with me, none of them could be found in the area described by the main PMC map; they had retreated to their respective private rooms. The only way to get to these rooms is by "teleporting" in, which requires a com mand like @join Shrimp-Fried.Ninja. Hoping to find out more about the postmodern condition, I joined the crustacean as a guest. There I discovered pomo culture is better experienced than described. I type, @join Shrimp-Fried.Ninja The Wanderer's Home PMC-MOO is also home to postmodern "events." One such event was hosted by a player called Ogre. Tarquin says, "ok everyone" Ogre's "suicide" was the culmination of a nasty PMC- MOO fight involving a group of MOO terrorists who fled PMC after their experiments with virtual society began to seriously annoy John Unsworth and the PMC wizards. The terrorists claim these experiments were meant to probe the nature of existence in a virtual community. The trouble began when Ogre and a few other players created what they called a terrorist class. The purpose of the terrorist class, according to Ogre, was to "experiment with factioning the community, developing semi-tangible classes which mimicked histor y or real life." People wishing to become terrorists read the following manifesto: %% TERRORIST CLASS PLAYER INSTRUCTIONS %% Terrorists acquired a whole set of nasty verbs, including "steal" (for robbing other players of their virtual objects), "ditch" (for planting stolen goods on an innocent player), "slogan" (for spewing a set of predetermined neo-Mao terrorist slogans), "ki ll <player>," and "bomb <player>." The bombs at first killed only wizards; then they were upgraded to kill anyone in the room, including well-meaning guests. Dropping a bomb set off a spewing of several lines of text -- !! -- after which hapless players were transferred against their will to room #310 as "eMOOgency services" carted them off to the hospital to recover. The terrorists wanted to confront the older, more staid PMC users. "They complained that new users were more interested in playing around and making things than talking about Post Modern Culture," says Ogre now. "I thought this was a shallow take on the s ituation, because we were living pomo, and more often than not it was a chance to explore it more deeply than by exchanging notes with other people verbally. I've always objected to the paper trail of academe. Experience fortifies theory." Ultimately, the wizards removed the terrorist class, and that's when things got nasty. A battle ensued between the few truly angry players and the wizards. A character named Smack created an object called the DarkWhole that, when activated, would sense who was in the ro om with it and produce disturbing messages. Here is a sample of what happened when a guest was "fed" into the DarkWhole: Feed DarkWhole with Guest This is the kind of programming that gets you in trouble. The solution adopted at first was punishment without due process. Offenders could be kicked off the system by being @toaded ("@toad" tells the computer to destroy someone's character. Only wizards have access to that command). One player, Sedate, created devices similar to the DarkWhole, except his were invisible; if a hapless player triggered one of them, the player would then be "locked" in place, unable to exit a loop of violently offensive tex t. Seeming to come from nowhere, the assault would go on for a half hour or more, spewing hundreds or thousands of lines of text, leaving the victim immobile, mute, and terminally frustrated. In the end these stunts proved too unpleasant, and Sedate was @ toaded without warning. This angered a lot of other PMC members, and a number of them went into voluntary exile. So, like so many other MOOs dealing with these kinds of problems, PMC instituted a democratic method of dealing with offenders. Now, if a play er is offensive, the victim can type @banish. A character with a certain number of @banishes associated with its name could get @toaded. Things seem to have settled down now over at PMC-MOO. Meanwhile, some of the former PMC terrorists have set up camp at Point MOOt, Texas -- a MOO created by Allan Alford, an undergraduate English major at the University of Texas at Austin. Point MOOt provides settlement space for long-term MOO users. Situate d at a Texas crossroads, Point MOOt is open to homesteading -- with a catch: There is a price for everything. First-time users are granted a small amount of credit to build objects, which corresponds to disk space and processing time. If an object is used by a lot of people, its creator is rewarded with more credits. Point MOOt opened in February and already has more than 250 players, who have built some 4,000 objects using their credits. These include a university, a radio station, a TV station (MTV, MOO Television, which has put together a history of the town), seve ral strip malls, an electronics outlet store, and a finance magazine called FOOrbes (which maintains a list of Point MOOt's ten wealthiest citizens). Alford is "contracting" to have utilities, roads, and other public services built. Since time is the only real commodity in cyberspace, the time that players invest in creating their objects is the real currency of Point MOOt's economy. The price of time is reflected in the prices people (or groups of people) charge for their objects. Players are divided into three classes. Players who build nothing are considered to be on welfare. Their homes are in public housing ("drab," Alford admits), and they get one building credit per week from the computer. Most players belong to the working c lass. They go down to the city "job bank," examine the list of objects that need to be built, and contract to take on the public work; in return the city pays them and gives them credit to build. (Objects built by the city are communal and free for everyo ne to use.) The last class is the capitalist class. These players build objects and "sell" them to other players. Useful objects get sold often. One player, named Warhol, has taken this one step further: Players "invest" in Warhol by giving him credits. He then builds very useful objects and sells them, using his profits to repay his investors. It is a sort of virtual stock offering. Even the wiz ard class is for sale -- really successful players can "buy" the position. Alford predicts that as more players join Point MOOt, the community will evolve in unexpected ways. He thinks issues of governance will arise soon (at the moment, Point MOOt is sti ll controlled by wizards), as more players invest time in the system. Point MOOt is monitored more or less constantly by social scientists interested in virtual communities -- a group likely to grow rapidly as MOOs become a more important part of everyday life. Jennifer Grace, for one, believes that MOOs are part of a gener al transition to a postindustrial world where information is the primary commodity, and that today's primordial virtual worlds provide a preview of what we may expect, IRL, in the future. EVERY DAY THE NUMBER of people using networked virtual spaces in education increases. The Internet as a whole now has 20 million users. At current rates (doubling every two years), the total could reach 160 million by the year 2000. Thes e users will be not only Americans -- they will be spread over the globe. In the course of writing this article, word got around, and I soon found myself receiving half a dozen e-mails daily from teachers telling me about another class, another project, a nother MOO. Educators of all stripes are beginning to explore what it means to teach in a virtual environment, and preliminary results from these early experiments are trickling in. They will be delivered at a variety of conferences -- the MLA and the Computers and W riting Conference among them. Teachers using MOOs report that almost all students enjoy using virtual space. For many of them, creating MOO prose is the first time writing is not a chore. They need to write to communicate with one another. They describe t hemselves and name themselves. Some build rooms of their own. What excites them is what excites so many of us: They have an audience. People read what they write. They have to in a MOO. MOOs have their limitations. They discriminate against people who can't touch-type. They also require students to "multitask." As John Unsworth explains, "The people who grew up listening to music on the headphones with the television going while doing th eir homework have a decided advantage here. They are able to handle three or four conversations at once, following the threads, while other people who are used to doing one thing at a time find it very stressful." Teaching students in a MOO can be difficu lt; fortunately there are several mechanisms for controlling MOO conversations. One, called "stage talk," allows people to speak to one specific person rather than the whole room; saying hello to David in stage talk appears as "Scott [to David]: Hello." A nother, "the yell," or "microphone," gags an entire class and allows only the teacher to speak. Perhaps most importantly, in MOOspace, faculty often lag behind students and allow unchecked information to be disseminated as fact. In virtual environments, m etaphor easily becomes truth, and the truth is rarely screened. Unlike other information-dispensing innovations such as the photocopier and the videocassette, networked virtual spaces are likely to fundamentally change academia, since as a mode of information distribution, MOOs may well prove as revolutionary as the m ovable-type press. Already, you can "publish" information without a publisher, certain that thousands may read your posting. How many people read you depends not on the decision of an editor but on how "useful" your information is, and how accessible you make it. Electronic information is uncontrolled -- it resembles a virus, passing from one medium to the next, using computers as hosts and telephone lines as the means of infection. It grows, it is built upon layer by layer, and no one person owns it -- i t is too ethereal, too mercurial, to possess. It belongs to everyone. There is no way to shut off this process. Soon, text-based networks will be complemented by image-based networks and hybrids of both. More and more information will be created and disseminated in cyberspace, and academic institutions will develop new tool s to channel it. When history revisits this era, Pavel Curtis and his MOO may well deserve more than a footnote. He may find himself alongside Guttenberg. David Bennahum is a regular contributor to Wired and The Economist. He is the author of In Their Own Words: The Beatles After the Breakup and k.d. lang. |

Get the full story: Visit "the best web site in the world" (Observer, UK) for a daily digest of the best writing on the web.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||